You are here

Research and Descriptive Reading - Visual Analysis

Primary tabs

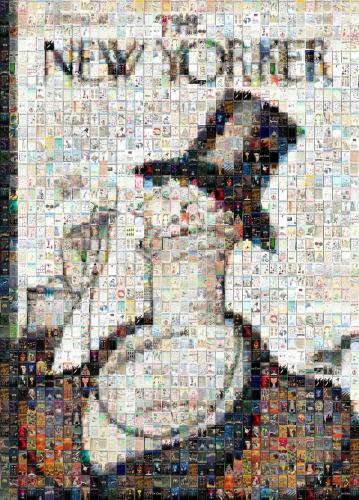

Piquef: Conde Nast, 2011

This plan puts student into groups of three or four and asks them to collaborate on generating a coherent analytical reading of a New Yorker cover image. The students present their readings to the class and then trade images and present a re-reading. Class ends with the groups reclaiming their original image, incorporating the different reading, and self-assigning research topics. The following class, the groups re-convene and then present a reading that integrates the two primary readings, bridged and nuanced through external research.

Building descriptive and analytical habits of mind

Identifying and avoiding evaluative modes of reading

Accepting uncertainty

Synthesizing divergent ideas

Networked classroom or student laptops, and/or a pile of old New Yorkers or similar images. You can also compile and distribute these images digitally.

Media console/document projector for presentations

**Note: this works best if you have made visual rhetoric exercises part of your course structure in the early weeks when you're introducing the "analysis" concept. If you haven't, you can set aside some classtime one or two days ahead of this to get some practice in with other images.

At the beginning of class, the instructor should review the differences between descriptive, evaluative, and analytical reading strategies. Emphasize the ways in which evaluative reading can disguise itself as analytical, and the obstacles to critical thought it can create.

--Divide the class into groups of 3-4

--Distribute New Yorker Covers. It's best if the instructor vets these for topicality, transparency, and complexity. It's a good idea to have a range of difficulties, but each image should have a clear current-events referent and be susceptible to at least two different interpretations. "Money Issue" covers and the covers published during the Occupy movement and major elections cycles are especially rich, although there are plenty of recent covers that take up higher ed and internecine sociocultural tensions that get really interesting too.

--You can have a written prompt if you like, but don't be too presctiptive. I simply tell my students to formulate a one-sentence description that states what the image is of/about, then to generate a kind of critical summary that points to specific visual elements and makes claims about how they contribute to a greater complexity of meaning. While they're working, circulate between the groups. if no one has questions for you, offer them some of your own. Be especially watchful for students who are skipping steps, or not working closely enough with the image, or being too general. Deal with these missteps by asking provocative questions about the grounds of their claims.

--Avoid being over-directive. This exercise is about keeping them in the space of discovery and description as long as possible, so questions should be formulated so as to throw them back into the text rather than push them towards conclusions. The typical undergrad is deeply uncomfortable with this space and if you give too many directions they will simply spit them back at you as "answers" in the presentation.

-- Give the students about fifteen minutes in their first group session to come up with a two-minute presentation. This seems like a relief to them, since they don't think they can fill longer time slots with "just this image." Inevitably, the groups will run over time. Be really strict. Time them with an alarmed stopwatch and cut them off after the two minutes. The fourth group to present will usually come in just at two minutes. This is a teachable moment about the time and space responsible analysis actually requires.

--Have the groups switch images and repeat the process.

--If you're being disciplined about time, you should have about 20-40 minutes to wrap up after the second round of presentations. (Ten minutes of housekeeping and introduction to the exercise, 30 minutes of group prep time, 16-20 minutes of presentation [assuming a class of 20-24 students], four minutes of transitions/slop time have been filled up so far.)

--Wrapping up:Have the groups reclaim their original image. Their assignments for next time will be for each student to find some relevant secondary source and write a 3-sentence description of it and its relevance to the group's image. At the beginning of the next class, the groups get a ten-minute final planning session, then give a 5 minute presentation.

--Give a prompt for this presentation, since it should do several very specific things.

--Present the group's original reading modified to integrate or challenge the second group's reading of the image in question.

-- Present at elast two secondary sources that give theoretical/critical and/or historical context to the image

--Offer a complex, nuanced, and analytical statement of what they believe the image is about, what it says, and how it fits into the larger context of the moment in which it was published.

--Browse the issues of the New Yorker in general.

--Be aware of the headlines that were current when the issue was published

--Have a stopwatch of some kind

--Be ready to evade requests for over-directive instruction

--Have some inspirational quotes about uncertainty and negative capability handy

In general, see the Full Assignment Description

I shy away from elaborate written instructions for this sequence because it's really about establishing comfort with a state of intellectual play. Written instructions become training wheels in this context. Because the stakes are very low, but kind of implicitly present in the whole economy of dialogue and idea exchange, I find such training wheels to be disruptive and counterproductive. Keep it all very verbal for this whole process.

This is not a lesson/assignment sequence that requires a lot of evaluation. In fact, evaluating the quality of analytical approaches should be left largely to class discussion. The way I approach this is to thank presenters and then ask the rest of the class where they'd take it next. Presentations that provoke the most energetic conversations become the examples you refer to in later classes, so there's a kind of ongoing reward system that does not punish lower-quality efforts

This exercise was a hit. Students respond pretty well to being given the thematic reins, and many of them respond really well to the oppportunity to argue. A lot of them remarked that the development of two co-existent readings for the same text, and then being asked to synthesize them, was a real eye-opener.

This exercise is also a great way to establish a collegial and collaborative learning environment. Be present, but keep your role in the realm of moderator/facilitator. Ask questions and insist on time limits for things, but try to avoid "correcting" readings unless they stray into major, fundamental error. Even then, it is usually better rely on the internal economy of the exercise. If one group goes astray, the next might correct them for you. Save these interventions, if necessary, for the endgame.

PBWorks/ some kind of blogging platform helps, but is not necessary, in bridging the classwork/homework divide. Make sure the group members make plans to be in touch, especially if you make the at-home portion happen over a weekend.

RHE-309k: Rhetorics of Truthiness is a broadly-conceived thematic intermediate writing course. It teaches the basics of critical reading, research, rhetorical analysis, and academic writing. Thematically, it focuses on the rhetorical strategies and topical questions surrounding the 24 hour news cycle and the question of bias through Stephen Colbert's provocative definition of truthiness: an argumentative quality that makes a claim "feel true" without any necessary connection to fact or 'Truth.'

-

- Log in to post comments