You are here

Contextualizing Web Research

Primary tabs

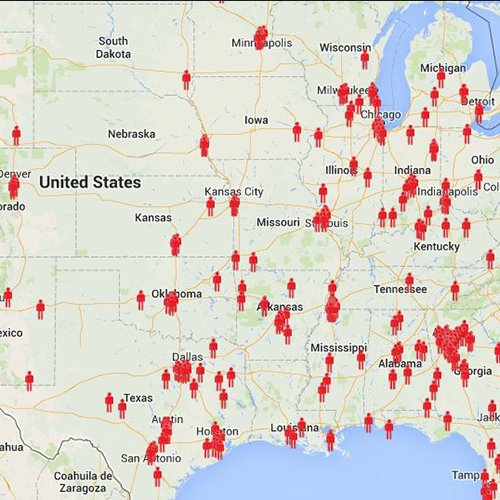

©2014 Google Map Data

Research in composition courses is often taught in a vacuum—a set of skills that can be used to write a college paper, but irrelevant to the “real world” outside. By contextualizing research that can be immediately used by citizens, we can connect these skills to social change, and hopefully teach students that these skills are necessary for a vibrant civic life.

Following the fatal shooting of Michael Brown, 18, in Ferguson, MO, and the police response to protests, a number of journalists drew attention to projects cataloging police shootings. Given that most police departments do not track this data, these journalists have begun crowdsourcing the collection of this important public information. These databases are large, and it would take a single researcher years to compile all of the information.

Ideally, this lesson should ground students in specific search practices as well as give them a sense for research "in the wild." The instructor should first walk the student through sound public web research practices. For this aim, instrutors could walk students through Google's Advanced Search features, paying particular attention to "this exact word or phrase" search area. At this point, it would also be helpful to have a brief discussion on phrases that may be used in police shooting reports. Allow students to generate these terms as a class, and demonstrate their efficacy.

Once students get a handle on this search of all webpages, the instrrructor can then move onto Google's Advanced News Archive Search. Before moving into the search, though, instructors should present students with the parameters ithey'll be searching within. The following websites provide crowdsourced spreadsheets of shootings by police:

- Kyle Wagner via Deadspin: Wagner also provides context for this database along with some ground rules for research.

- Fatal Encounters, compiled by D. Brian Burghart. A Gawker article provides the context for this database. Note that the website has a specific procedure for contributing. Researchers must first use the database to find those names that have yet to be researched. Next, they need to use the people search to ensure someone else hasn't already researched this shooting. Finally, the researcher must submit a request via the submissions page. (This process became necessary when someone fudged some of the original shared document.)

This discussion could take a number of routes. Given that the US has no national database (and most local police departments do not keep public records of this data), students could discuss the importance of such crowdsourced data. What are the benefits of such a database? How could it be used to improve public safety? Could it be misused? Is such a database even necessary? Questions of this sort get students thinking about the public role of research and citizenship.

Ultimately, though, students will choose a shooting to research and apply the search skills outlined above.

Instructors may want to familiarize themselves with Google's Search Tips, as they provide instruction in more directed web searches. Additionally, instructors may want to peruse the various crowdsourced research projects to determine

1. Choose a website from the above two.

2. Choose one of the shootings to research.

- Note the name, location, and date, if available.

3. Using the advanced search features, fill in the missing information on the incident.

I would suggest not evaluating this exercise. It's intended to get students thinking about search strategies and the role of citizen research in a democracy.

-

- Log in to post comments